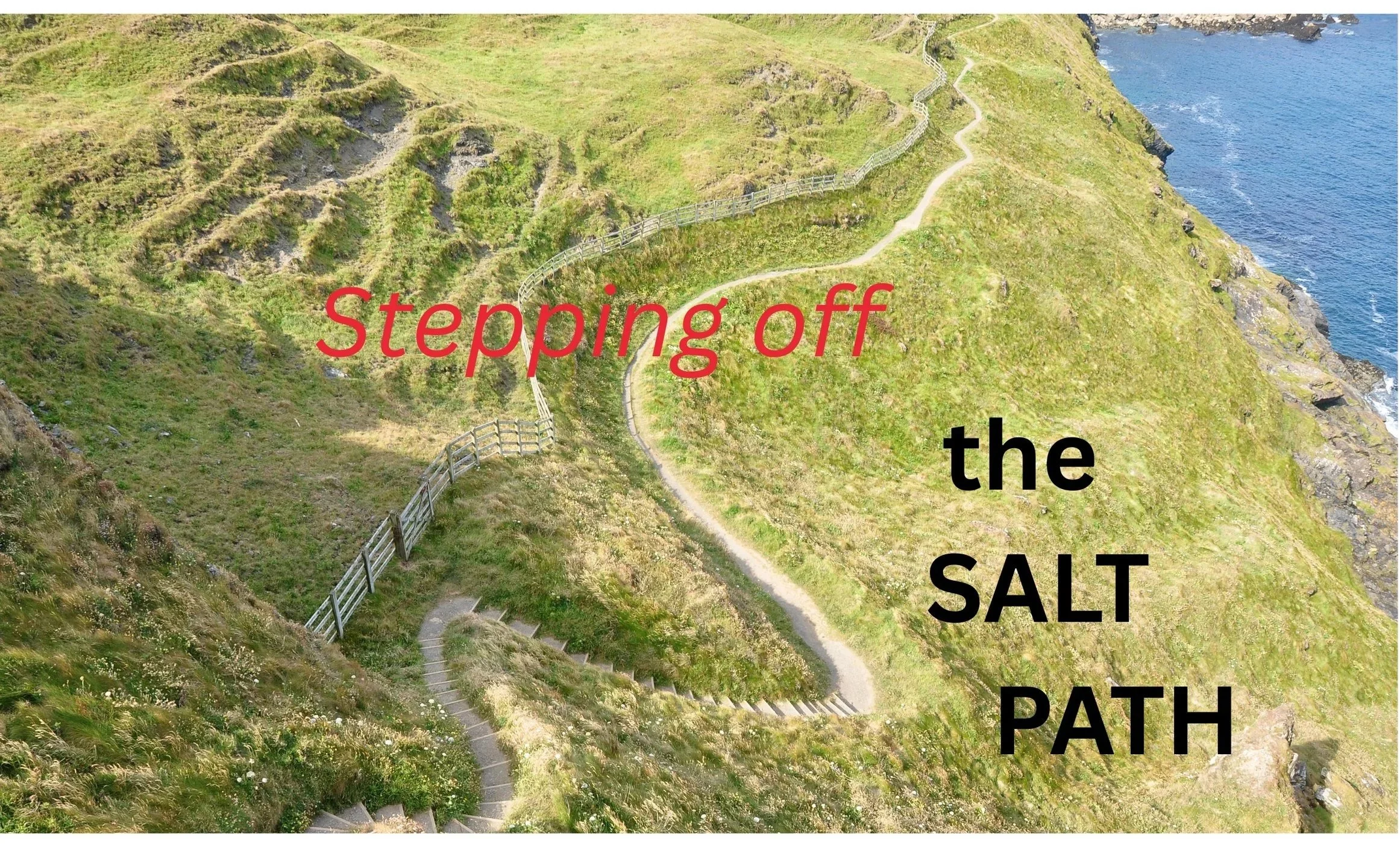

Stepping off the Salt Path

Where does the recent furore about the veracity of The Salt Path lead us? I don’t mean whether Raynor Winn’s account of walking the Cornish coast with her seriously ill husband will ultimately be deemed true or false. More importantly, how is this controversy reshaping our understanding of memoir and the nature of truth in literature. We live in an age where truth itself appears fungible, when established fact can be dismissed with the flick of a soundbite as ‘fake news’. How, then, are readers expected to engage with memoir – as sleuths of truth or conspirators in calumny?

Of course, the line between fact and fiction has always been blurred. Writers have long borrowed from real lives, incomplete records and hearsay. Historical novelists thrive on this challenge. Kate Foster framed The Maiden, longlisted for the 2024 Women’s Prize, as a fictionalised account of the actual relationship between Lady Christian Nimmo and Lord James Forrester as little evidence remains about Nimmo’s demise uncoloured by a patriarchal view of women in 17th century Edinburgh.

Creativity, after all, is the writer’s craft. As Mark Twain joked, ‘Never let the facts get in the way of a good story’. A travel writer may concertina events or change chronologies to add pace and drama. And publishing, with its hunger for sales and platform, drives such behaviour. Note how the drums announcing the ‘hot debut’ go silent as a publishing house ducks negative headlines underlining a poor commercial decision. The Salt Path publisher Michael Joseph (Penguin) was quick to pass the buck to Raynor Winn.

As a writer, blending imagination with nuggets of lived experience is a challenge. With memoir, the stakes are even higher. The label promises a pact with the reader, this happened. We may have once been admired for authenticity but no longer. ‘Reality television’ is anything but. Social media turns the minutiae of daily life into curated public performance. Words, like images, can be manipulated into click bait.

Fabricated memoir is nothing new. Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year (1722), Maria Monk’s lurid Awful Disclosures (1836) and the forged Hitler Diaries (1983) were bestselling ‘truths’ exposed as invention. Now The Salt Path enters this debate. By calling her book a memoir, Raynor Winn signals it is lived experience. To be fair, memory is a tricky collaborator.

We edit, deliberately or subconsciously, to fit a narrative. My brother recalls the cinema trip we missed when my mother broke her wrist, I relish how she vaulted a wall in her late fifties for the hell of it. Both are true. We filter events to serve a purpose, to present ourselves in a particular light.

When first writing about my psychotic episode, I too called Mistress Pieces a memoir. That was naïve. Some of my clearest memories were hallucinations. In retrospect, I knew my encounter with aliens on the New York AirTrain at JFK was imagined. However, did my husband kick down our bedroom door at 2 am or, shoulder it open? A kick makes for better drama; it doesn’t make for better truth.

And I am, by temperament, a storyteller. I embellish. I invent. In the first part of Mistress Pieces where I describe my ex-husband’s ‘attack’ shattering me into conversing bodily pieces, it is allegorical. My fingers didn’t talk while my head lay averted in a corner, but much of what they recount is autobiographical. My father did suffer from poor mental health and alcohol dependence.

How then to balance memory and metaphor without confusing the reader?

The second part of Mistress Pieces, recounting a visit to a friend in the US, is built on real events. But no, she did not drag me back from casting myself naked into a creek. More likely, she may have considered pushing me in; while psychosis had a certain beauty to me, it took its toll on others. How can this be conveyed in a memoir without resorting to constant disclaimers - ‘I imagined’ – slowing the pace and losing the reader?

And whose truth counts anyway? Friends and family have different views of my psychosis. We know that witnesses to an event often disagree wildly. Reality is, to some extent, constructed and contested. In memoir, relationships can be damaged where one person’s ‘truth’ feels like another’s misrepresentation.

And, sometimes, another’s memory is more colourful and commercially attractive than our own. In the third part of Mistress Pieces, after body and mind have healed, I describe a string of sexual encounters. Are these true or abstracted from a friend’s retelling of ‘shagging like a rabbit’? For my children’s sake, I marked my manuscript with highlighter: hallucinated scenes, metaphor and allegory, imagination. I shocked myself by the extent of neon; so many characters, events and thoughts I had simply invented.

I am relieved I resisted labelling my book a memoir but instead categorise it as an experimental novel based on a queer love affair and madness. The choice feels more honest. I created people, scenarios and conversations to serve a darkly humorous story, whilst remaining faithful to a sequence of events - of sorts. If readers want the literal truth, they’ll need to ask my kids for the neon copy.

So, was I really shagging like a rabbit? Remember, I’m not walking in the footsteps of The Salt Path. The work makes no claim to be a memoir; the truth is mine to know.

Mistress Pieces by Jen Hyatt. Published by Fingerprint Editions, 2025 https://www.fingerprinteditions.com/publications

Jen Hyatt is a writer, performer and activist. She is a member of the Society of Authors. Mostly she writes for adults, but has also published the King of Kazam, a modern fairy tale picture book for children; wrote and performed in a one-woman comedy show about Modern Sin at the Edinburgh Festival; and hosted two popular podcasts featuring women writers.

Her non-fiction writing has been published by the Guardian, Forbes, and the World Economic Forum.

Previously, she worked as a social entrepreneur founding over thirty nonprofit ventures internationally, raising £50m, and winning numerous awards including Red Magazine’s Digital Woman of the Year and Freeman of London. Her media and public speaking appearances include the BBC, TED and Davos. She was born queer and working class on a farm in rural Dorset and now lives in Edinburgh.